Sentences on Creating with AI

When creation is effortless, meaning is the only thing that matters.

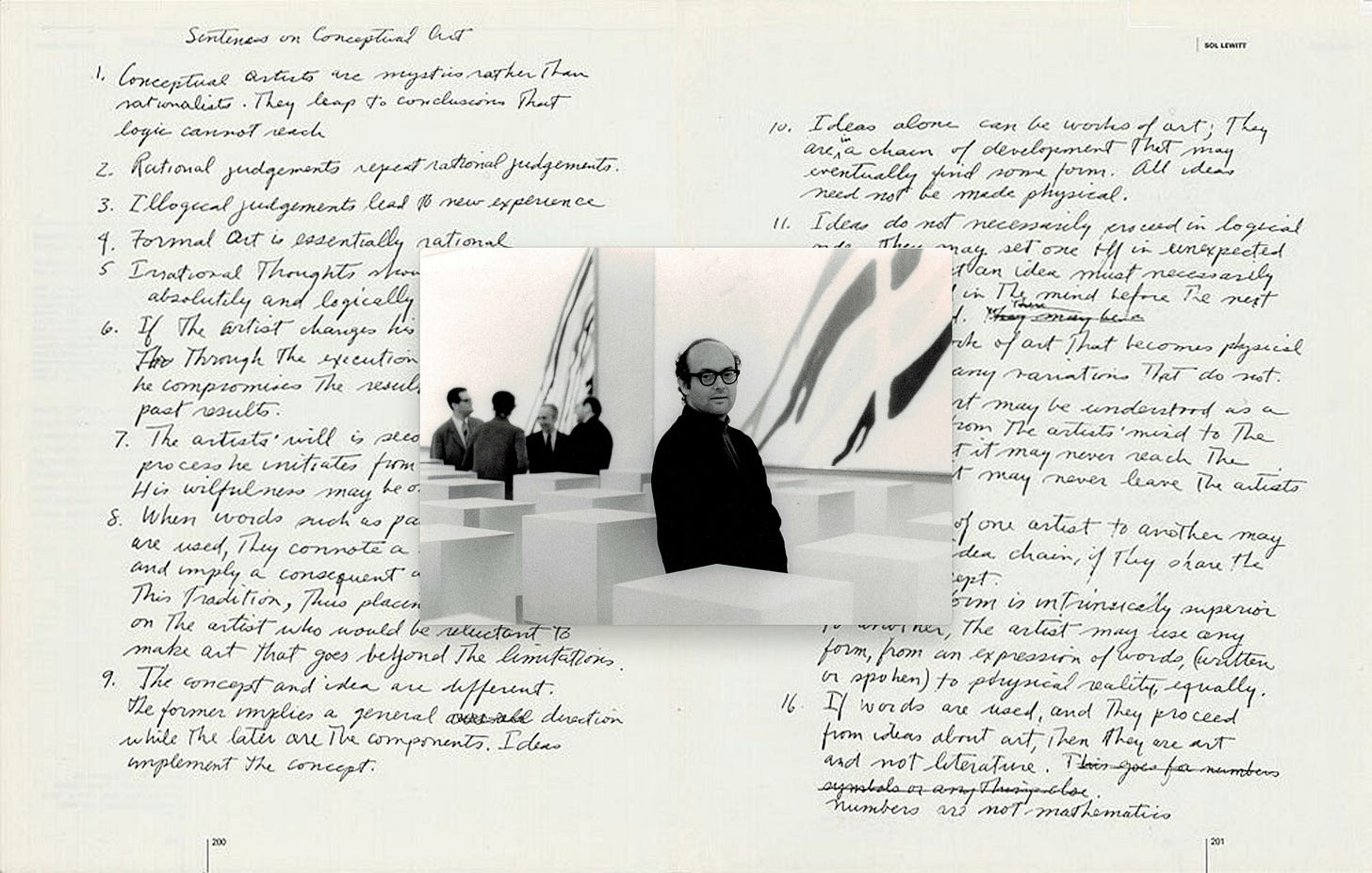

I first came across Sol LeWitt’s Sentences on Conceptual Art when I was working as an art director trying to understand the difference between a concept and a tactic. This work stuck with me. Over the years, I’ve internalized them as creative philosophy, and, as a compass for how to think. LeWitt believed that the idea behind the work mattered more than the execution. At the time, that felt provocative. Now, it feels obvious and, maybe, more urgent than ever.

Sol LeWitt was a pioneering American artist who helped define Conceptual Art in the 1960s and 70s. He was a trained draftsman, deeply influenced by architecture and systems thinking.

His writing, Sentences on Conceptual Art, challenged the traditional notions of authorship, skill, and aesthetics. Instead of making the work himself, LeWitt often wrote instructions for others to carry out, turning the concept itself into the art.

LeWitt makes a clear argument: the idea behind the art is more important than the final form. He challenged the tradition that places value on technical execution, material, or visual skill. Art begins and ends with thought.

The concept is the artwork; whether or not it’s physically made is secondary.

His “sentences” are a kind of manifesto, laying out a creative hierarchy where intention trumps output.

When tools can do the making for us, his ideas feel less like a relic and more like a roadmap.

This way of thinking aligns closely with how we create today, especially with tools like AI, which are only just becoming possible at this scale. When anyone can generate a visually striking image, a user ready front end, or a shippable product flow at the push of a button, what separates noise from substance is the clarity and strength of the idea behind it.

Just like LeWitt wrote in the ’60s: “Ideas alone can be works of art... All ideas need not be made physical.” (Sentence 10)

If the concept is sharp, the execution becomes a detail, not the defining trait.

So when I started thinking about what LeWitt might say today about AI tools, generative output, and what it means to make something, I didn’t start from scratch. I started from what I’d already learned from him. This is my attempt to bring that thinking forward: to see if those original sentences can still hold, even when the hands that make the work are no longer our own.

If LeWitt had access to the same intelligence tools we have now, he’d be writing prompts. Or maybe something new, with the same sentiment about a different medium.

Sentences on Creating with AI

inspired by Sol LeWitt, for AI-driven creative work

Those who create with AI are driven by ideas, not aesthetics.

Outputs are easy to generate; meaning is hard to get right.

Unexpected prompts or edge cases often surface the most human truths.

Frameworks give structure, but not significance.

The strange, intuitive idea is often the one worth following.

Changing your intent midstream usually reveals a lack of intent.

The maker's ego must step aside so the system can reveal its own logic.

Labels like “art” or “feature” come with baggage. Let the idea lead.

A vision guides direction; individual prompts, flows, or pixels bring it into focus.

A raw idea—a feeling, a question, a contradiction—can be the work.

Concepts don’t unfold in order; they collide, regress, and resurface. Make space for that.

Every decision not to generate or ship something is as important as what you do show.

Output is not the work. Interpretation is.

One prompt, one friction point, one sentence—can unlock someone else's best idea.

No medium, format, or model output is inherently better. It’s only better if it serves the idea.

If the interface, artwork, or model response aligns with the concept, it’s design. Otherwise, it’s noise.

Anything made with care, reflection, and purpose belongs in the conversation.

Judging early work with late-stage metrics leads to false conclusions.

Systems are reshaped by each person who pushes against them.

The best AI creations don’t impress—they shift how we think about authorship and intent.

When we see our own tools in a new way, we invent new uses.

You won’t know what your idea really means until someone else reacts to it.

Misunderstandings are fertile ground for invention.

What you meant matters—but how it’s received matters more.

The creator’s interpretation is just one of many. Trust the multiplicity.

Your collaborators—including models and systems—may surprise you. Let them.

A good idea can live in structure, prompt, delay, or deletion.

Once an intention is clear, let the process run. Don’t micromanage out the meaning.

Interfering with generative flow too much weakens its signal.

If it feels obvious, you might finally be getting close.

When the prompt stays the same but the response shifts, the system is revealing its depth.

Novelty without clarity is decoration.

A sharp idea can survive crude output. A vague one can’t survive anything.

Perfect polish often hides a lack of risk.

These sentences are not art or product—they’re a mirror.

The posted image is a remix I made from two photos and is used under the fair use doctrine and is not claimed as my own.

Sol LeWitt at Documenta with his work Seriality. Photo by Maria Netter Basel,

Sentences on Conceptual Art, 1968 - The Museum of Modern Art