Product Design with AI: Balancing Product Metrics and Human Value

Focusing solely on productivity overlooks a huge part of the human experience. This isn't new in Product Design, but AI's capacity to amplify work output should not make more work.

The views expressed here are my own and do not reflect the position or policies of my current employer.

The Pursuit of Productivity vs. Purpose

With my 15 years of experience in design, crafting brand stories and building productivity tools, I’ve noticed a strong focus on hitting metrics that aim to boost user efficiency. This goes beyond my immediate span of control at work and speaks more broadly to work culture and the industry at large. My job is to build products for the masses. These products are often judged by the amount of efficiency they bring to people in their day-to-day productivity grind.

I don’t believe people are defined by their work. I believe they are defined by what motivates them. Efficiency can be measured to fulfill product goals, but the very nature of the products we build should not be about doing more work—it should be about freeing up more time to do the things that motivate us, things that give our lives meaning.

This focus on efficient productivity and “impact” can often cause us to forget the deeper need for meaning in work. Hustle culture glorifies constant activity and leaves little room for leisure, reflection, or genuine connection. There is an illusion of productivity in hustle culture—the harder you work, the busier you appear, the better off you are. Often times, the reward for hard work can be promotions, a bigger salary—all good things. It does, however, lead to more work.

Take, for instance, a hamster in a hamster wheel. The faster it runs, the more progress it thinks it’s making, and yet it ends up exactly where it started. Similarly, many of us find ourselves caught in cycles of constant activity, mistaking busyness for meaningful progress.

I like what I do. I like my career. Curiosity motivates me and I feel fortunate to have a role that allows me to be curious every day. I have the opportunity to learn from some of the most brilliant people in the industry. I get to learn how people work in the context of work. My job allows me to build innovative ways to help people do their job. However, I do not work for the opportunity to be productive. I work for the opportunity to learn from others. I work to support my family and create meaningful experiences for them. Providing experiences for them is what motivates me beyond the daily grind, and it's this type of motivation that truly defines all of us, as humans.

AI is at the precipice of unlocking a new level of proficiency, productivity, and so much more. I don't think we have even scratched the surface with this technology. By its very definition, technology is meant to make our lives better: to free us from repetitive, mundane tasks so that we could focus on pursuits that give life meaning. However, the emphasis on the advancement of technology has shifted towards relentless growth in productivity, where the outcome of technological progress is judged on how much more work it enables us to complete.

The problem with this shift is that instead of using the efficiency gains to enrich our lives, we find ourselves using those gains to pile on more work, losing the opportunity to engage in the truly human activities that technology was supposed to make space for. It's possible that we’ve lost sight of technology’s true purpose. Our definition should be refocused on enriching human experiences and fostering creativity, relationships, and exploration, not just productivity.

The Metric Trap

In product design, metrics are what drive many design decisions and backlog prioritizations. We measure task completion rates, steps to completion, and error rates, using rich telemetry tooling and using guidelines like Hick's Law and Krug's Law.

While these metrics are useful to help guide product direction, over-reliance on these traditional measures can lead to designs that prioritize efficiency at the expense of user well-being. They often fail to capture the emotional aspects of the user journey, such as satisfaction, engagement, or the sense of accomplishment after completing something.

Imagine you're a carpenter, and your toolbox only contains hammers. Now, every problem you encounter looks like a nail because that's the only tool you have to work with. Similarly, when we rely too heavily on metrics in product design, we risk treating every user problem as something that can be solved by simply measuring and optimizing efficiency. It oversimplifies complex human experiences into basic, measurable units. It may lead us to focus solely on improving these metrics, potentially at the cost of addressing deeper user needs and motivations.

Over-reliance on these metrics can send us down a path that takes us further from our, and our user's, motivations. By examining what these metrics fail to capture, we can begin to see the full scope of human experience that is often overlooked in our pursuit of efficiency.

What Metrics Fail to Capture

The focus on metrics can dehumanize work, turning people into extensions of the tools they use. It's like being a cog in a giant machine—precise and efficient, but the output alone can be devoid of any personal meaning or fulfillment. We need to rethink how we use metrics to ensure that they serve people, not control them.

Imagine a gardener measuring success solely by how quickly they plant seeds, ignoring the beauty of the flowers that bloom. In product design, this might translate to focusing on how quickly a user completes a task, rather than the satisfaction or creativity the process might inspire. Meaning is deeply subjective and varies from person to person, making it difficult to quantify through conventional efficiency metrics.

The Individualized Nature of Purpose

The individualized nature of meaning is a crucial aspect to consider in product design. What brings fulfillment to one person may not resonate with another, making it essential to create flexible, adaptable solutions. Consider how different cultures, age groups, and personal backgrounds influence what people find meaningful. A young professional might find meaning in career advancement, while a retiree might prioritize family connections or personal hobbies.

This diversity in what constitutes meaning presents both a challenge and an opportunity for designers. We must create products that can cater to a wide range of individual needs and preferences, allowing users to customize and personalize their experience in ways that align with their values and goals. By acknowledging and embracing this individualized nature of meaning, we can move beyond one-size-fits-all solutions and create more inclusive, empathetic designs that truly resonate with diverse user bases and dimensions of identity.

Understanding the nature of intent, motivation, and meaning can help us reframe our approach to product design as something where the tools we use at work and the time we spend living need to be in balance. But at work, where our time investments are placed where we can clearly define impact on productivity metrics, how do we prioritize features and new areas of capability that allow technology to do what it is supposed to do?

Shifting Focus from Efficiency to Value

Understanding User Intent and Motivation

AI has the potential to help us understand deeper human motivations and support users beyond immediate actions. With capabilities that can analyze how users interact with tools, platforms, and workflows we can quickly understand their work-related intentions. Beyond task completion, however, we can use these same capabilities to uncover underlying motivations like collaboration or creative exploration.

Having a work and personal AI assistant, we can potentially unlock a more holistic balance between work and play. For example:

Task prediction: AI can learn which tasks users prioritize based on historical patterns, context, or urgency, allowing it to suggest relevant actions or resources to streamline workflows.

Goal alignment: By analyzing a user’s broader goals (e.g., completing multiple projects or achieving team milestones), AI can adapt the tools and environment to help them meet these objectives more effectively, offering personalized shortcuts, recommendations, or collaboration opportunities.

Behavior insights: AI can detect when users are stuck or switching contexts frequently (e.g., between tools), identifying potential pain points or inefficiencies. It can then suggest solutions to enhance focus or productivity, helping product designers align features with real user needs.

There is a difference between user intent—what a user wants to achieve in the short term—and motivation—what drives them in the long term. Understanding this distinction is crucial in designing products that not only fulfill tasks but also resonate emotionally with users. By emphasizing the balance work and life we can create deeper connections between users and products, narrowing the gap between task completion and personal fulfillment.

Just like a good book resonates not just because of its plot but because of the emotions it evokes, effective product design should go beyond functionality and touch the user's deeper motivations.

Practical Approaches to Designing for Meaning

As we shift our focus from efficiency to meaning, it's crucial to translate these conceptual ideas into actionable design strategies. By implementing these techniques, we can start to bridge the gap between an academic or theoretical understanding and tangible user experiences, ensuring that our designs not only meet functional requirements but also resonate with users on a deeper, more meaningful level.

Audits with Empathy

Tools like Empathy Mapping and Critical User Journey (CUJ) audits can help us focus on the underlying motivations and the more meaningful aspects of the user journey rather than solely optimizing for efficiency. These tools help us to understand users’ needs, emotions, and moments where they might seek personal value. Empathy mapping should also consider how users can create space for themselves—moments of reflection, emotional recharge, and genuine personal engagement while using the product.

By using AI as an empathy machine, we can leverage its ability to understand these underlying motivations that drive everyday life, where motivations are personal and holistic. For example:

Lifestyle pattern recognition: AI can learn routines, habits, and preferences across different life activities (e.g., Work, exercise, hobbies, socializing) and offer meaningful suggestions that align with the user’s broader life goals, such as well-being, learning, or balance.

Emotional insights: By interpreting tone or engagement levels, AI can understand users’ emotional states and adjust its recommendations to align with their needs in that moment—whether it’s offering mindfulness exercises during stressful times or suggesting leisure activities when users seem overwhelmed.

Life priorities: AI can help people balance work and personal life by understanding their overarching intentions, like prioritizing family time or self-care. It can integrate these personal goals into everyday decisions, making tools and products feel more supportive and human-centric.

Imagine designing an app that offers the same sense of calm as a well-tended garden—it's not about maximizing activity but about providing a space for reflection and growth. A good example of this is the 'Headspace' meditation app, which focuses on creating a calm environment for users to reflect, recharge, and grow, rather than just optimizing for becoming calm as fast as humanly possible.

It’s also valuable to consider how established design principles can inform our use of data and metrics. Looking more deeply at the philosophy Dieter Rams in the context of data science, we can potentially gain fresh insights into creating meaningful, user-centered AI products.

Balance and harmony are essential. AI product design should not add unnecessary features that distract from the core purpose. Instead, it should be intuitive, supporting meaningful user experiences by doing exactly what is needed—and nothing more.

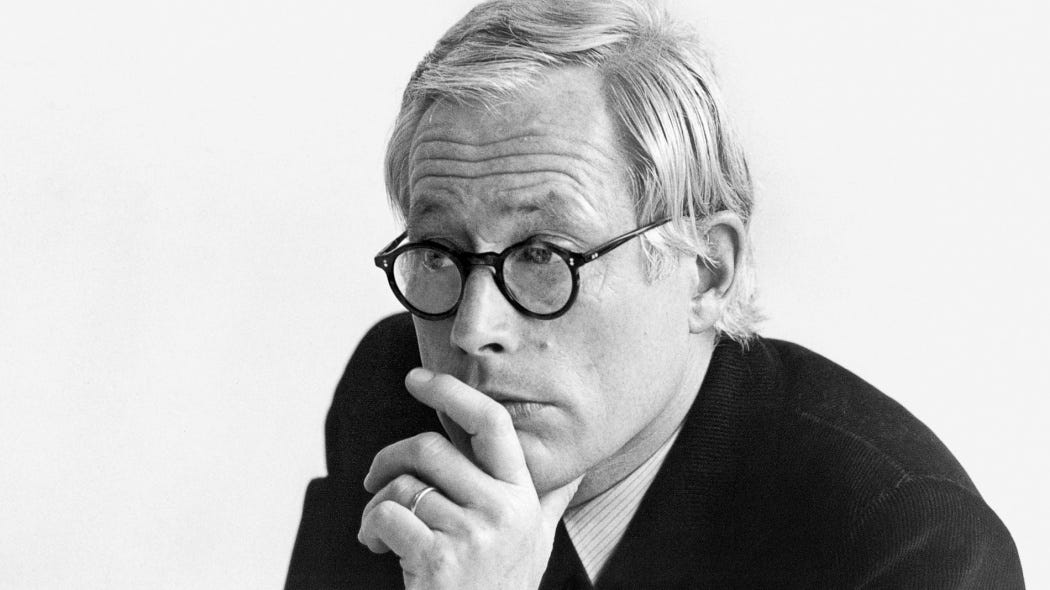

If Dieter Rams was a Data Scientist

In December of 1976, Dieter Rams gave a speech titled “Design by Vitsœ” in New York City about his work with Vitsœ. He also outlined much of his design thinking, which later evolved into his 10 Principles for Good Design.

“Everything interacts and is dependent on other things; we must think more thoroughly about what we are doing, how we are doing it and why we are doing it.” - Dieter Rams

Rams' design principles, when applied to data science and AI, offer a unique perspective on how we can use metrics to enhance human value and experience rather than focusing solely on efficiency. If Rams were a data scientist today, he might prioritize metrics that align with his philosophy of creating products that provide long-lasting value and enrich human life. Some examples include:

Time to Value: This metric focuses on how quickly users derive meaningful benefits from the product, emphasizing the importance of immediate user satisfaction.

User Satisfaction and Emotional Connection: These metrics align with Rams' emphasis on creating products that resonate with users on a deeper level.

Cognitive Load Reduction: This metric would measure how effectively the AI simplifies complex tasks, adhering to Rams' principle of making products easy to understand.

Long-term Retention: This aligns with Rams' focus on creating enduring designs, measuring how well the product continues to serve users over time.

In practice, this could mean designing AI systems that prioritize clarity and simplicity, measuring not just task completion times, but also adapting to user satisfaction and emphasizing the long-term impact on users' lives and work processes.

Giving Time Back

Breaking Free from Hustle Culture

Hustle culture has ingrained in us the idea that productivity is the ultimate goal. However, AI can help dismantle this notion by optimizing mundane tasks, which should in turn give time back that will allow users to focus on what truly matters.

Reframing productivity as something that serves our personal lives rather than the other way around can change how we think about work.

With the advancement of AI agents and agentic workflows, users will have access to tools with subject matter expertise comparable to many professionals. This should mean that humans will have more time to be with other humans and not more technology.

Building Products that Allow Users to be People

These products should be designed to reduce pressure rather than add to it. By moving away from constant tracking and monitoring, technology can become a tool for genuine, meaningful engagement instead of a source of stress. Designing products that let users simply “be” without feeling the constant need to be productive is crucial. Think of a cozy reading nook—it's not meant to produce anything, but it offers immense value in the experience it provides.

Technology should create similar spaces for users to engage meaningfully, rather than driving them toward relentless efficiency. By freeing users from mundane tasks, AI enables them to focus more on fulfilling activities, like spending quality time with family or creative pursuits.

Technology Should Support Life, Not Dominate It

The true role of technology is to support a meaningful human experience. Good design adapts to users' lives and becomes part of their routine in a seamless, supportive way. AI can be a force multiplier - designed to enhance quality of life, help reclaim time and provide opportunities for people to pursue what truly matters. As we look to the future, the potential of AI in enhancing meaningful human experiences is vast. We might see AI systems that not only optimize tasks but also learn and adapt to individual users' values and goals, suggesting ways to incorporate more meaningful activities into daily routines. Technology must be about enriching life, not just optimizing it.

Reflect on your own use of technology. Is it helping you lead a more meaningful life, or merely maximizing efficiency? Challenge yourself to choose technologies that enrich your experiences and bring genuine value to your life. As designers and users, we can strive to create and adopt technologies that not only make us more productive but also more human, fostering creativity, relationships, and personal growth in the process.

While these ideas and thoughts are my own, and not associated with my current role and company and organization, it would be a huge miss if I did not provide additional reading and recent articles that resonate with my lived and professional experience and share similar sentiment.

There are decades worth of information on this topic, but the articles below are top of mind. Read these:

During my time at Google, I had the opportunity to work with the Responsible AIUX organization and the PAIR Guidebook team and craft principles that focused on this topic. Read here: User Needs + Defining Success

Stop inventing product problems, start solving customer problems